Aya is nine, and she thinks like an artist. She’s Ash’s best friend.

She’s visiting from Waiheke for a chunk of the summer. Waiheke is the tiny island—just north of Auckland—where Ash, my seven-year-old son, and I wound up living while waylaid in New Zealand during Covid for a couple years. She flew here in the metal bird with her whole family: two moms, two baby sisters. My house is full of Kiwis and noise. My dad, Jack, is here too. Four kids, three moms, one grandpa. The fridge is spilling over, the couch is covered in Weird Kid Things, there is very little floor space and very little thinking time, and I love it, because the house and my heart feel alive. Aya’s moms are both half-Māori, and they love and talk easily. They’re making me homesick, and happy.

They’ve been here about a week now.

Aya often wakes up first and trundles up to my bedroom at 6:30 a.m. A few days after they arrived, everyone still groggy and jet-lagged, Aya came up to my bed at the break of dawn.

Aya.

She’s waking me up out of a nightmare, literally. I don’t think I’ve been having too many nightmares, but then again, who knows; maybe I have been, and I just needed a nine-year-old around in order to notice.

It was a stupidly standard nightmare: someone had kidnapped Ash and taken him overseas. I could do nothing about it. As I got the news, I was also driving a huge white van full of music equipment, alone, and I was late for my own gig. I realized, while barreling along at 70 miles an hour, that the brakes of the van weren’t working. I did not know how—or where—I was going to stop. I’d lost my child, I’d fucked up my work, and I’d lost control.

I wake up sweating. Aya patters over to my bed. Her eyes are sleepy and her long, thick black hair is all mussed.

“Hi, Auntie Amanda.”

Everybody in your wider important family-friend circle in New Zealand is an Auntie or an Uncle. I love that.

“Hi, Aya. I love you, sweetie. You woke me up. I’m glad because I was just having a nightmare and now I’m not anymore.”

Then she clambers up into my huge pile of pillows for a cuddle and kōrero (that’s what the Kiwis call an important chat).

“What was your nightmare about?”

I shove a pillow under my head so I can sit up and talk to her, and take note of my still-sweaty post-anxiety-nightmare body. God, I love her little Kiwi accent. I love how much she loves it here. I love how much she loves Ash. I miss the Kiwis. I miss the island.

I miss the sound of their voices. “Eggs” sounds like “iggs,” and “text” like “tixt.” “Yes” sounds like “yis.” Everything is more adorable coming out of the mouth of a Kiwi.

“It was about … oh, Aya. It was just a really sad and scary nightmare. I’d lost control of stuff. Getting divorced is hard.”

She looks at me quizzically, then frowns.

“What? Wait a minute, you and Uncle Neil are getting divorced?”

Oh, fuck. She doesn’t know. But that doesn’t make any sense. She and Ash were best friends for ages even after Neil made it into New Zealand, and she knew we lived in separate houses. But I suppose we didn’t talk about it very much, and she mostly saw Neil and me together. So how could she have known we were divorced unless her moms told her?

So here I am, still nightmare-sweaty in bed, having to break the news to Ash’s best friend that we’re divorced, and I’m feeling like I have to explain this right or I fuck everything up. Divorce is weird, and kids are smart. I grew up with six divorces: my dad had two, my mom had one, my new stepdad had already had one, his recent ex-wife had already had one, my second stepmom had already had one … the main thing I learned from all of them is that it’s better to talk about it and get it wrong than not talk about it. None of them really talked about it. Here goes.

“Yeah, Aya. Neil and I got divorced a long time ago. Over three years ago. When you met us both on Waiheke, when you and Ash made friends through the fence, we had already been divorced for a long time. We were already living in different houses when Neil came to the Motu, remember? That’s why I had the Ice Cream house and Neil had the Writer’s cabin.”

She’s an intense, direct Kiwi. I brace myself. She stares straight at me.

“Why did you get divorced?”

I breathe.

“That’s a really good question. I’m glad you asked it. I’ll tell you. Mostly, we just had a really hard time agreeing about stuff, and we found out we were really bad housemates. But we still really, really love each other, even though that might sound weird, and we still both really, really love Ash. We love Ash, but we are gonna do it from separate houses. And we both love the bejeezus out of you and your whole Whānau.”

Whānau (“fah-no”) is another one of those brilliant Māori terms for an extended family and friends circle. We don’t really have an English word for it, which is telling.

She snuggles under the quilt with me and grabs her own pillow. Her brow knits.

“I don’t think I want you and Uncle Neil to be divorced. Why do you have to be divorced?”

“’Cause it’s just the right thing. But it’s hard, Aya. There are days when it’s really painful, and it’s hard for Ash too, because having parents living in two different houses can be really annoying. And since you’re gonna be here all month, maybe you can help him and help take care of his heart because you’re his best friend. Did you know that when I was a little girl, my parents got divorced?”

“No.”

“My parents—Grandpa Jack and my mom, Kathy, who you’ve never met—got divorced when I was just a baby, even younger than little Chinami. I wasn’t even a year old. But my sister was five; she was about Miwa’s age. We were really sad about it. Divorce is just … hard.”

She says: “I’ll be right back.”

And she hops out of my bed and runs down the stairs to the living room. Everyone else is still asleep.

What’s she doing? I think. I lie there, still in my puddle of post-nightmare ache, hoping I’ve done a good job at explaining my divorce to a nine-year-old in a non-traumatizing way.

I stare at the ceiling. I think about Ash, and whether or not he really understands this divorce. I try to remember being seven. Back when nothing really made sense, but it didn’t not make sense either. It all just was.

Three minutes later, Aya comes back up the stairs holding a piece of white printer paper.

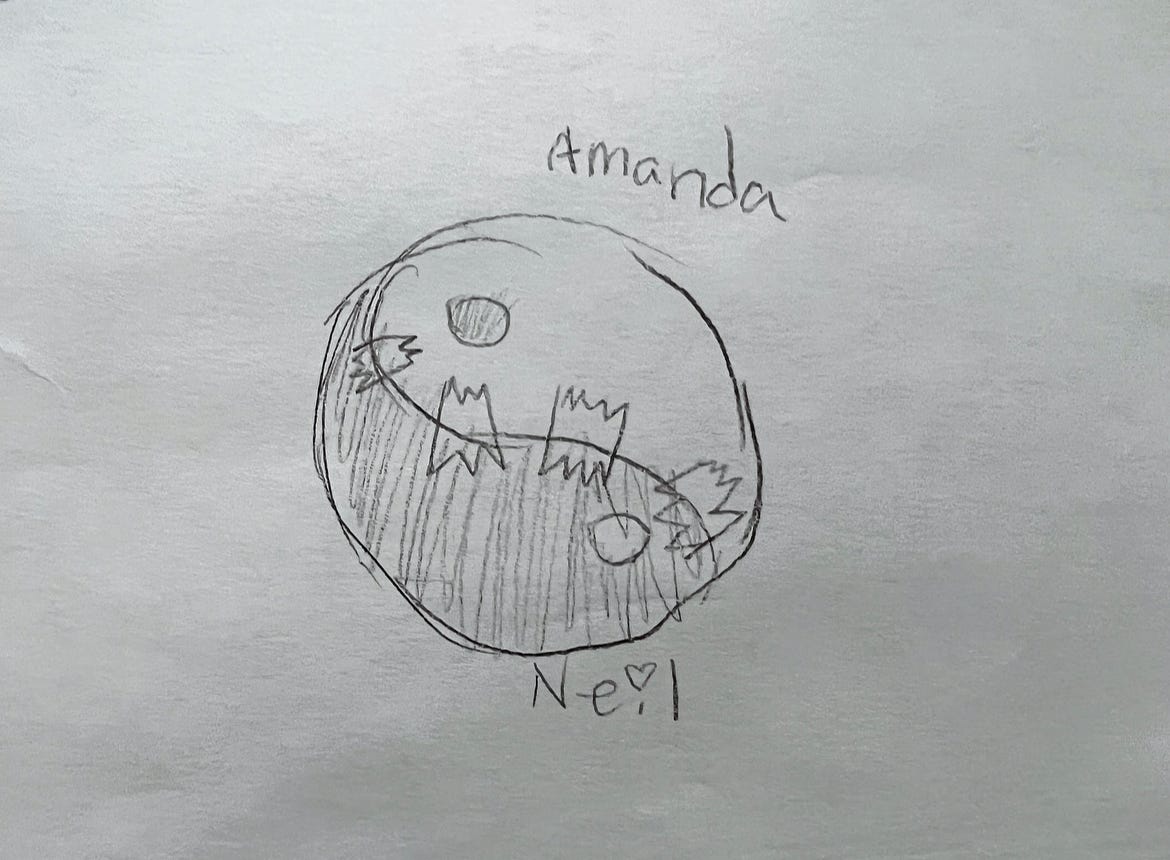

“I made you a drawing.”

She crawls back into the bed and hands it over. I look at it and don’t quite understand it. I see a yin-yang, and something else that I can’t make out.

“What’s that sorta spiky part?”

“Sellotape.”

Sellotape is what the Kiwis call Scotch tape. The way she says it, it sounds like “sillotape.”

“OK. And what’s the rest of it?”

“It’s a drawing of your divorce. This white part is you. But then that little black part is Neil’s heart, which is still inside of you because you still love him. And then that big black part is Neil, but then there’s that white bit which is you because he still has the part of him that loves you, and then there’s all those pieces which is Ash holding you together. Hence the Sellotape.”

Did a nine-year-old just say “hence” to me?

In the Kiwi accent, it sounds like “hince,” and I just want to break down crying and hold her raw, honest wholeness in my arms. For all the reasons. Because she gets it. Because she’s so practical and forthright about it all.

But mostly because her instinct was to put all these feelings into a piece of art, and make it on the spot, and give it to me. I get that instinct. I know.

“Aya, I love you so much. I love this drawing. You’re a really, really good artist.”

She beams.

“Aya. I want to show you something.”

I reach over beyond her. The sweater is squished under my pile of pillows. It’s my boyfriend’s; it’s beige and brown, wool and scratchy, used and abused, a snowy Icelandic design around the neck. Aya knows him; he was just at the house for a couple days, hanging out with me and all the kids. She dubbed him Uncle Brendon.

“This is Uncle Brendon’s sweater. He left it here on purpose when he went back to Boston for work, because he knew I’d miss him. And this is a really special sweater, do you want me to tell you why?”

She nods.

I get up and put the Hence the Sellotape drawing—which I am already planning to frame and treasure deep into old age—on the mantelpiece, and I get back into bed and pull the quilt back over both of us.

“See these places on the sweater where it’s had holes but it’s been all stitched up?”

She takes the sweater and I show her the mended spots, the knots and tangles of different yarn, some of the mended spots camouflaged so well you’d barely notice them. Brendon showed all of the spots to me when he left for Boston, when he left the sweater, when we said goodbye on the lawn. Some of it mended by friends, he said, some by his mom.

I miss his mom.

“See this spot here, where it’s a little mangled and you can tell it had a hole? This one was mended by Brendon’s mama. And she’s gone now; she died just a couple years ago, during Covid. And he really misses her, so that’s what makes this sweater precious. Not just that he loves the sweater, because he has a special story about finding it, or because he was wearing it the night that we found each other again. He loves it because it’s been broken and fixed, and his mama did the fixing, and now the fixing is the important part. Just like your drawing. The fixing is the love part, Aya, the part that makes it beautiful and real. Hence the Sellotape.”

She takes the sweater softly in her hands, looks at the visible mends, knots of brown yarn, then looks at me, nods, and says solemnly:

“Yes. Hence the Sellotape.”

………..

Over the next few days, I tell the story to various friends, musicians, overnight guests. It gradually became a meme in the halls of my house.

Good morning. How’d you sleep? Badly. Wanna coffee?

Hince the Sillotape.

Do you need a hug?

Yes.

I move the drawing to the downstairs mantelpiece; it reminds us.

To be visibly mended.

To show the stitching, the scar tissue, the fixing, the work of love.

What you have weathered makes you painfully beautiful.

It is the mend that makes you precious.

Hence the Sellotape.

This Substack page is a home for my long-form writing, and I would be so touched if you subscribed. I sometimes use it as an advice column (hince “Ask Amanda”), too.

If you’re interested in my music and wider body of work, and you’d like to follow EVERYTHING I create—beyond the writing—you can also join my Patreon, where I am currently approaching 20,000 patrons. Over there, I post several times a week: thoughts, song demos, musical discussions, videos, podcasts, collaborations, webcasts … all sorts of things. It’s a wonderful place where the community gathers, and it provides the vast majority of my income. If you’d like to become a patron, you can explore all the options (starting at $1/month) here: https://www.patreon.com/amandapalmer

………..

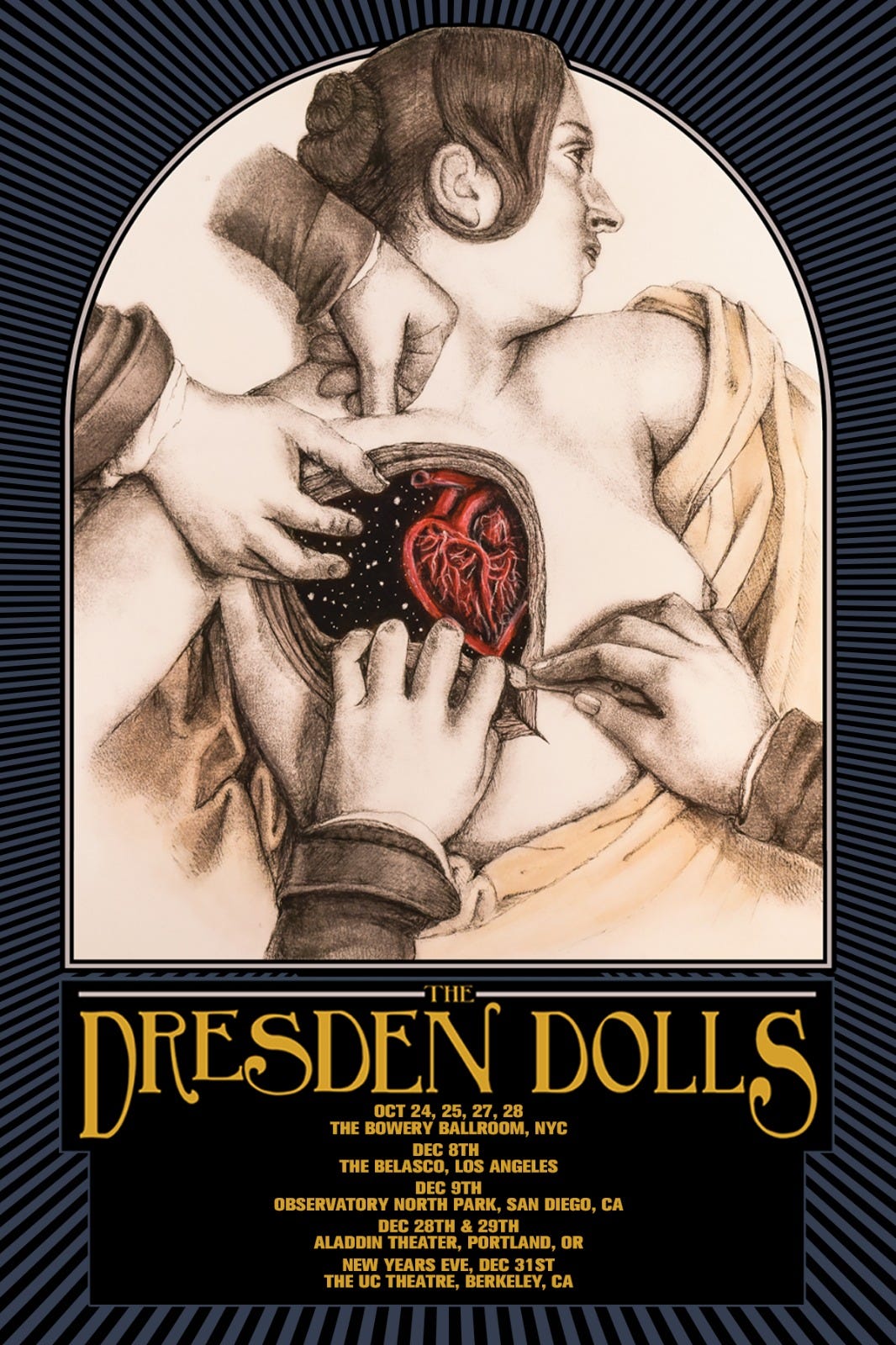

UPCOMING TOUR DATES

WITH MY BAND, THE DRESDEN DOLLS:

OCT. 24 - Bowery Ballroom, NYC - SOLD OUT

OCT. 25 - Bowery Ballroom, NYC - SOLD OUT

OCT. 27 - Bowery Ballroom, NYC - SOLD OUT

OCT. 28 - Bowery Ballroom, NYC - SOLD OUT

DEC. 8 - The Belasco Theater, L.A. - JUST ADDED

DEC. 9 - The Observatory Theater, San Diego - JUST ADDED

DEC. 28 - The Alladin Theater, Portland, OR - SOLD OUT

DEC. 29 - The Alladin Theater, Portland, OR - SOLD OUT

DEC. 31 - NEW YEAR’S EVE @ The UC Theatre, Berkeley, CA

All tickets at dresdendolls.com

….

THREE NOVEMBER FRIDAYS @ THE RUBIN MUSEUM OF ART:

All tickets at The Rubin Museum of Art’s site.

♥️

"Four kids, three moms, one grandpa. The fridge is spilling over, the couch is covered in Weird Kid Things, there is very little floor space and very little thinking time, and I love it, because the house and my heart feel alive."

My body physically relaxed upon reading this. <3 <3 <3

That child is a worldly treasure. Searchlight soul. Glad to hear there's all kinds of good things happening around you. :)

"Divorce is weird, and kids are smart."

If you're into Old books where guys with white beards carry around tablets of rules you recognize that this should have at least been in the top ten.