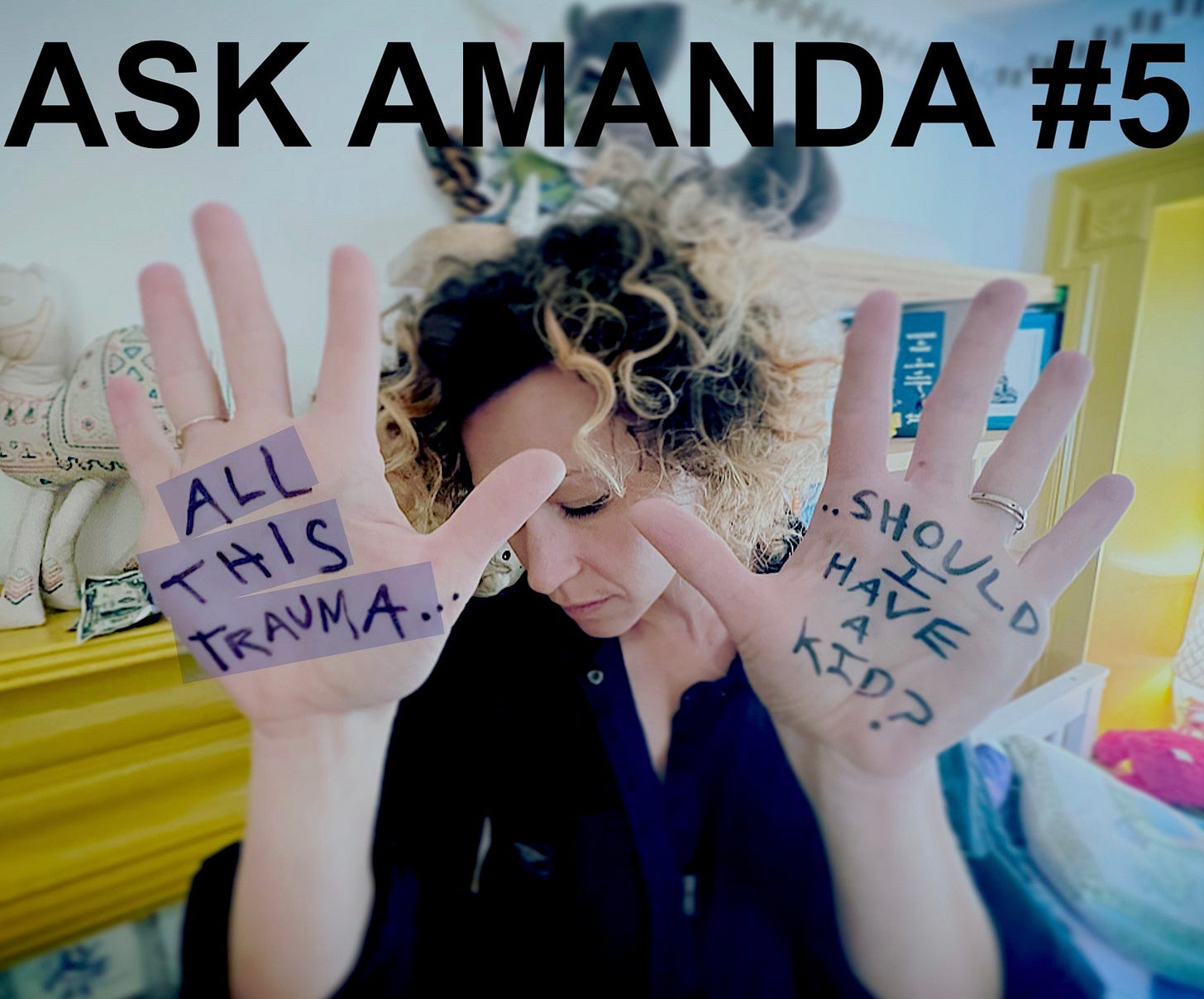

ASK AMANDA #5: Should I have a kid?

I’m a trauma survivor, the pandemic changed things, and now I’m on the fence.

Photographs of Coco Karol — choreographer, mother, and friend — by Amanda Palmer

Hi Amanda,

A couple years ago, my husband and I decided that we wanted to have a baby, and set a date to start trying. Then the pandemic happened, and then I had a series of health problems, so it’s been on hold, and the waiting gave me too much time to overthink it. Now I’m not so sure.

When I think of myself 10 or 20 years from now, I see a mom. I’d like to have a family, since I was pretty much on my own before I met my husband. The problem is that I don’t like being around children. Babies and teens are great, but children (around 2-10 years old) are hard for me to be around, probably because of my own childhood trauma. (I’ve read that unconscious sensory triggers can remind my brain of its own childhood, which was rough.) I know I’ll be a good mom when they’re older, but I’m afraid I won’t be a good mom to a young kid because I won’t want to spend time with them. Should I listen to that impulse? Am I unable to give a kid the mom they deserve?

Thanks a million,

L.H. or “Doubtful in Nebraska”

P.S. I hope you pick me! I see a lot of stuff about women who know they want kids, and about women who know they don’t want kids. Women who are in between and undecided aren’t talked about enough. It’s a lonely position to be in.

………..

Illustrations by Sarah Beetson

Dear Doubtful,

Oh, man. I love you. I hope this letter finds you, and finds you well.

I have found that not everybody is honest about — or perhaps, can really articulate — how it feels to have a kid. Especially if you’re a person who’s experienced hardcore trauma, or has a difficult family, or health problems, and the list goes on.

I know so many women who have agonized, and then agonized over the agony itself. I myself have agonized over the agony, and so has Sarah Beetson, the illustrator for this column, and (in a first for Ask Amanda) she’ll add her own thoughtful response — and artwork — below.

First of all, Doubtful, I want to acknowledge how complex, lonely, and disconcerting this indecision can feel in your brain and your body. With the current shitshow surrounding reproductive freedom in America, there is a corresponding poetry in how little this complexity is acknowledged, held, and respected by people in our communities.

We do not live in a culture where the decision to have a baby is easy. Divorce rates are high, families are weird, people move around and change their agendas constantly, and communities are splintered diasporas. There are few guarantees and fewer safety nets.

It does indeed take a village to raise a child, and our villages are burnt-out and leveled. I can deduce, from what you wrote about being “pretty much on my own” before you met your husband, that you probably don’t have a dandy, helpful, supportive family. You are not alone in this experience. So many of my friends with kids have to deal with family estrangements, traumatic wounds, and a desperate improvisation around where stability and support will come from.

This is such a critical thing that people do not understand about The Agony of whether or not to have kids. Giving birth to a child into a happy little neighborhood with a wide, tight-knit network of helpful kin is a different matter than looking at your wonderful partner, alone, and saying: okay, let’s do this, let’s make a family by ourselves.

We can all fantasize about that old-school village (can’t you just see them? Belly-laughing while dishing out plates of handmade pasta for one another, strumming mandolins, pouring wine, bouncing children from grandma to auntie to grandpa to cousin, sharing rich, happy family histories around a huge fireplace big enough to fit a car? Why, in my imagination, is this family ALWAYS ITALIAN?).

If you happen to come from a complicated or splintered family — with a history of abuse, trauma, alcoholism/addiction, and so on — you have an extra one-two punch when considering the choice of whether or not to have kids. You not only lack the ready-made village of endless safety nets and fireside homemade pasta, you also have a grief-stricken void to contend with when you feel lonely and isolated. Especially when you see other happy families parading around looking well-adjusted. (But note as well: it’s never what you seem. Those happy-looking families are often buried in horrific hidden stories.)

In addition, if the trauma you experienced as a kid is still in the landscape as an active threat (and you’re not estranged from your family), you may even feel like you need to protect your children from your own kin, lest they carry on inflicting the pain that you yourself had to endure. That feeling can be extra-lonely on top of having little or no family support.

There is very little public celebration of women who decide not to have kids.

There should be.

Women who choose not to have kids are often seen as selfish, yet the opposite argument could easily be made. Having a child and raising one — from where I stand at the moment, as the mother of a 7-year-old — can feel like an incredibly self-indulgent act. You aren’t a full and focused part of the workforce, you’re a drain on resources, you’re taking up more space and eating more food, and you’re always flailing around, desperately needing help from the community. It is funny to me that society would deem having kids a “selfless” act.

I didn’t have a kid until I was 39. Grandmother age, in many cultures. I was one of the “childless” women.

Women who deliberately choose not to have kids give the world a different kind of power and abundance; they can forge a different kind of thoughtful relationship with their communities without the grind of motherhood slowing them down, a grind that, if you want to be a present parent to your kid, can effectively knock you out of the adult world for a long handful of years.

Women who don’t have kids contribute in a totally different way. I toured and sang and wrote and connected with other human beings for years. I simply would not have been able to do that had I had children. I don’t regret it. It all has to be acceptable — all of these choices — or we are buying into a patriarchal narrative that ultimately cages and punishes all women. Nothing rankles me more than people who whisper, “It’s so sad that she never had children,” and that whispering usually comes from women. When I hear people saying that — and they’re often from the older generations — all I hear is the painful mark of a patriarchy that forced women to believe that their value was measured predominantly by their efficiency in the reproduction department. Make babies, have value. This is what men have wanted us to believe for eons.

So back to The Agony.

We are given, as women in this society, so little emotional support and consideration in these difficult choices, and yet so many people want to celebrate the general theoretical existence of babies. Yay, babies! These theoretical babies — who will indeed turn into real, live kids and grown-ups — often wind up existing at the expense of the mental, physical, and emotional well-being of the parent. I’m not gonna bullshit you, and many parents will joke about this: on a bad day as a parent, you sometimes feel like you cease to exist. You feel numb and lifeless and erased. You feel like a blurry, thankless, identity-less host to a parasitic, hungry, angry, ungrateful, totally vulnerable, and smelly little creature. A creature who you have been told by society that you must unconditionally love and protect. Sometimes — like, 99% of the time — you can feel that love. But let’s be real. People sometimes throttle their children and leave them in dumpsters.

It isn’t all unconditional love and rainbows, clearly. Darker forces are also at work.

So let’s talk about the dark.

I agonized about whether or not to have a baby all throughout my 30s. Everything about the decision called the shape of my own existence into question: what I wanted my future to feel like, the way I felt about my partner and his own struggles, the fear about who would show up to support and help, the doubts about my own career and mastery over my own work hours, and, like you, the raw and unsettling deliberations about the painful parts of my own history, and how those painful parts informed my feelings about kids.

I wasn’t ever a “kid” person. I liked them, and I loved seeing the occasional cute baby, but I didn’t have many children in my life growing up (I was the youngest of four), and I lived a touring troubadour life-style that had very little exposure to little ones. In my late 30s, I saw the biological clock very clearly ticking on the wall, but I did not feel a biological clock ticking. I did not yearn to be a mother. I hadn’t gone through life desperately wanting to have kids, and for a long while I was perfectly content with the idea of staying child-free. It seemed like a no-brainer. I wasn’t yearning, so why do it?

Before I had my last abortion — which I talked about in detail onstage during my last tour in 2019 — I seesawed and agonized. I went back and forth for weeks.

This would be amazing! I wanted to have a baby! Wait, no. I did not want to have a baby. No, wait, it would be a great adventure! No, wait. It would be hell on earth. I had a book coming out! How would I promote it with an infant to take care of? Wait: what kind of person was I, if I was even considering choosing book promo over a baby? Clearly not the kind of person who should have a baby! My partner was much older — he was veering into literal grandfatherhood himself in those days, since he’d had a set of kids when he was young — and I didn’t know what all of that would mean. What if I wound up having to care for this kid by myself? What if Neil just … died? What if the kid was born with a fatal illness? What if I hated being a mother? What if I wasn’t good at it? What if nobody helped me with the kid? What if I didn’t even like the kid? What if my art got banal and boring? WHAT ABOUT THE CLIMATE CRISIS. What the fuck was I thinking, bringing a new life into a dying world?

I agonized and agonized and thought and thought, and, like you, I overthought. I went slightly off the deep end.

I wanted someone to come in, do the math, come up with a correct decision, and tell me what to do. In the end, I decided that if the decision itself was this agonizing, I should probably just step off.

So I had an abortion: the very ordinary kind that didn’t involve rape or incest or a woefully abnormal fetus. I just took a deep breath and decided I wasn’t ready. I didn’t want to have a kid. Not at that moment. Having that abortion felt painful, the end of a possibility, but it also felt incredibly empowering. I wasn’t going to have a baby just because I was afraid of being crippled by regret. I still look back at the decision with a mixture of melancholy, pride, and relief. I’ve had to defend the decision again and again, and the more I am asked to defend it, the stronger my resolve becomes. My body. My life. My choice. The end.

A year or so after that abortion, my feelings changed. I’m not sure why; very possibly because I got practical matters out of the way. I gave birth to the book I’d been busy creating. I had time, all of a sudden, to think more carefully about the topic of babies without one actively growing inside me, which felt a lot less stressful and panicky. I decided that I was as ready as I’d ever be, so I took the plunge and I did it. I was lucky to get pregnant at 38 without any fertility treatments. I had little Anthony, or Ash for short, at 39.

That was seven years ago.

I’ve felt called on to try to explain what it’s like here — over on “the other side” — ever since I got here. I’m more short on time than I ever could have imagined. But it’s why I chose yours out of all the questions I’ve been asked for this column. I feel I owe it to you, and to all the people who tried to advise me on my way.

You know me, I like to talk to people about feelings. Honest feelings. Frightening feelings. Shameful feelings. Back in my late 30s, while I was trying to figure out what to do about whether or not to have a kid, I had hundreds of conversations with parents. I asked everyone I could think of. I really wanted people — especially my artist friends — to tell me the truth, the real truth about what it FELT like to be a parent.

So I interrogated. I knew parents, so I picked up the phone and asked them. I asked people in the street. I asked people on the internet. The answers came, but there was a lot of contradictory information. The more I was told, the more confusing it all became. The pros and cons seemed to pile up in equally tall mountains.

I asked older parents whose kids were all grown or far away, or even dead. I asked new parents with screaming babies. I tended to listen most closely to the parents with little kids — this age group that you, Doubtful, actively fear. They represented the hardcore experience I was about to actually have over the next few years if I gave birth. I wasn’t interested in how it would feel 40 years from now. I wanted to know: how is it, really?

One of the recurring phrases was You’ll never regret doing it.

And yet. I’ll always remember the one friend, a professor at a university, saying, “You know, Amanda, you’re really not allowed to say it, but I wish I hadn’t had a kid. At the same time, I LOVE MY KID, and I’d never want to vanish her existence now that she’s here. But I wish I hadn’t done it.” I was shocked. And really impressed. This went against everything other people seemed to be saying. I’d hung out with him, and I knew that he actively and wholeheartedly loved his kid, and he was a really good dad.

I wondered if maybe there wasn’t something multitude-containing about the very question. You could clearly utterly love your kid and still profoundly miss being a kid-free person. This theme started to emerge: tired, unshowered, bedraggled parents looking at me wistfully, saying things like, “Well, it’s a cliché, but it’s the hardest job you’ll ever love.” And I would stand there thinking, “Are you saying that because you have absolutely no choice but to say it, because you know you can never take your baby back to the store?”

Some of my tired, unshowered, bedraggled parent friends were a little more nuanced, a little more philosophical. “Well,” they’d say, “it’s gonna totally reorganize and fuck up your life. But you won’t mind that much, because your ego will have gone through the shredder. It sort of brainwashes you, but in a lovely way.”

I am now that tired, unshowered, bedraggled parent. I now agree with the people who said that. (I am actually very excited I got to shower last night. It’s been that kind of week.)

Let me also remind you: the world is full of extra-painful illusion right now because of social media. Do not believe the charming parents and children of the internet. Do not believe Instagram. Those photos you see of smiling, bedheaded, chocolate-smeared children online? Those moments are real. But rare. Those parents take 50 photos of their children looking shitty, distracted, red-faced, and irritated before they find the one joyful and charming photo to post. The whole story is not shown.

You’re not seeing photos of the sleepless nights, the shrieking howls, the vomit and the shit in the bed (often at the same time), the shards of shattered and expensive china at your friends’ apartment that the baby managed to find and throw across the room. My kid is one of the most delightful people I’ve ever met, and he also twists the knife into my heart deeper than anybody else can. He’s going through a massive upheaval and change in his life right now, and dealing with culture shock on top of that. The things that come out of his mouth — aimed directly at me — can create more suffering at the core of my heart than the worst bullying I’ve ever endured. Kids can be the cruelest sadists on this planet. It’s torture sometimes. And so lonely.

Now ask me: Do I regret it?

………..

You said: “I’m afraid I won’t be a good mom to a young kid because I won’t want to spend time with them.”

Well, Dear Doubtful, many of my own nightmares came true.

I wound up in New Zealand, for upward of a year in total, taking care of a scared 5-then-6-year-old in the midst of a terrifying and unpredictable global pandemic. This had not been the plan. My co-parent was gone.

I was alone, the apocalyptic scenario played out.

There was the upside: we lived in a Covid-free New Zealand for 14 months, with no virus, no masks, and no social distancing, and Ash got to go to school and play with kids unhindered by and blissfully unaware — at most levels — of the pandemic. But it was also my worst nightmare come to life: I was alone with a kid, and help was not on the way.

And dammit, I’d chosen to do this. I’d chosen to have a child, and I’d made the pact with myself that if it all went to hell, and I wound up raising this kid alone, I wouldn’t regret it.

Like many solo parents in the pandemic, I had to — for the most part — let go of my career. Since Ash’s birth, I had been trying, and sort of succeeding, to juggle it all: to write, to tour, to play the piano, to run my patreon, to impress upon people that I could do it all. When Covid hit and I found myself alone with Ash, I simply couldn’t do it “all.” I could barely do anything but survive. There was lockdown. There were stretches of time where it was just a blur of food and laundry and dishes and sleepless nights and then more food and laundry and dishes. For many days, weeks, months, I had to set down any agenda other than raising the kid. My business, my other relationships, my desires, the emails in my inbox — it all went to hell. I set it all down and I took care of the basics. I did just enough work in the cracks to pay my bills and keep my community up to date. But mostly, the worst fear came true. Having a kid ate my career.

Ask me now, again: do I regret it?

Well; something happened to me, while I was in New Zealand, something changed. My career was surely eaten, but perhaps it also needed to be devoured. I had been, admittedly, flailing around and going too fast. I had to accept that to be a decent parent for this pandemic kid on this island in the middle of nowhere, I was going to have to let go of a lot of expectations I’d had about myself, my values, my priorities.

I had to let go of my striving ambition and my desire to be constantly regarded as a successful, busy, important lady moving around in the grown-up world. I became the thing I’d most feared: a basic bitch at the supermarket, just a tired mom with a tired kid, reading the backs of peanut butter jars and praying they’d have the kind of kale my kid would actually eat, and hoping for little more than a day without drama and unexpected twists. I started going to bed at 7 p.m. and waking up at 4 a.m. so I had time to do all the housework. I had a borrowed piano in the house, but I almost never played it. I was too fried, and I felt too guilty about the mess, or the pile of toys on the floor, or the rotting food in the fridge, or the clothes that hadn’t been washed.

This is what I feared would happen! I KNEW IT. I would become boring!

But the penny continued to drop. I had to examine what was driving my desire to be so un-boring in the first place, and I, of course, slammed smack into my own trauma and past, and my own self-important obsession with seeming interesting and important to other people. Hello ego, my old friend.

You were talking about your childhood trauma.

This is where we get to the heart of your question, Doubtful.

It is our traumas — which lead to our anxieties, our paralysis, our self-doubts — that make the agony so agonizing. When you worry about “not liking your kid,” I can assure you, it is almost stupidly simple: you will like your kid, most of the time. You may not like your kid all the time, and you may not want to hang out with them all the time, but under all the mundane pain of parenthood, you’ll probably love them all the time. Evolution will really help you out with that one; it’s a documented scientific fact. We are preprogrammed to find our own kids intoxicating and loveable, even when they drive us batshit crazy. Trust the science (and also trust the other parents here who will likely weigh in below in the comments).

You are obviously a person who’s not afraid of facing and grappling with the past. You’ve done the work and identified your own trauma. The fact that you are empathetic enough with yourself to step back from a potentially hurtful situation (bringing an unliked kid into this world) is almost a paradox: if you have the sort of empathy to even have these worries, you probably also have the empathy to bring a kid into this world and do the constant, clunky dance of accepting imperfection and self-forgiveness.

Or to put it another way: if you’re even asking these questions, you’re more emotionally prepared to have a kid than most people out there.

So take a deep breath, remember all the work you have done to understand yourself and your trauma, and listen to me for a second:

If you incorporate your trauma compassionately into your parenting, it will be one of your most powerful tools as a mother.

You will never be able to change the past. Trauma is horrific. The wounds run deep and the echo is infinite. I know.

So much trauma is intergenerational, passed down again and again. When we’ve done the work to peek under the hood with compassion, we can always see this. There can be something incredibly healing about raising a child, a new life, a new story, a new chance to put a loving halt to the cycle of pain.

The experience of seeing your child growing — into a 3-year-old, a 5-year-old, a 7-year-old — is like a mirrored time machine. Your child will take you by the hand and lead you straight into your own past. Back to the site of the trauma. Back to the age when the bad things happened, when suffering rained down on your own, fragile heart. It can be the most terrifying thing. But, trust me here, it can also heal the wound at a depth no other medicine can reach.

You are the adult now. You are no longer the powerless little one. To simply see your own child’s resilience in the face of suffering can be healing. It is immense, to be the loving, tender force that you yourself needed in those moments of trauma. To whisper to your child, “You are safe, you are loved, everything is fine” can work some alchemical magic: your own voice can carry a healing bandage to those old wounds through the time machine of your kid, and soothe your own old, seemingly unreachable scars.

You do, of course, have to be careful not to use your child as a therapeutic tool. It’s not their job be your therapist.

It’s your job to help them out; and hope for some healing as a by-product. If you spend too much time whispering, “You are safe! you are loved! EVERYTHING IS FINE!!!” into your kid’s ear, you’ll drive them fucking nuts in a whole new way (believe me, I’ve seen this happen). It’s a dangerous reversal: your desire to protect your own kid from the trauma you experienced can turn you into a helicopter parent, terrified at every turn that the Bad Thing will happen, and leaving you with the feeling that you must be some kind of around-the-clock watchdog for your child’s fragile self. This can fuck your kid up, too.

So just accept that you’re going to do an endless tightrope dance between letting your child wander into the world of danger (and you know the danger is real) and holding them back from experiencing the fullness of what the world has to offer them.

This all sounds very nice and neat, doesn’t it? But. Also. There can be very dark days, when you’re tired, and out of patience and kindness. Your trauma creeps in and grabs the steering wheel.

On the most terrible and taxing days, you’ll be tempted to become the monster you fear. You’ll be tempted to replicate the nightmare-song of trauma. It will threaten to suck you in like a siren. Sometimes, the words you most feared hearing as a child will dance, hot and jagged, on the tip of your tongue as you stare, enraged and exhausted, as your little child smirks at you and tells you she despises you for ruining her life.

But if you slow down, and you take a deep breath, and you think about all the trauma and healing you’ve been through, and you consider — before speaking, before acting — what those hot and jagged words would have meant to you when you were 3, or 5, or 7, you may pause before losing your shit at your kid.

You might not pause. You may lose your shit on certain days. Don’t worry about that. It’s fine.

But on other days, you may pause. And that pause, that moment, is the miracle. It’s the grace and the hugeness of healing your own trauma, of not passing down the pain, whether your temptation — on your worst days — is to be physically punishing, or verbally hateful, or smothering and needy, or distant and cold as ice.

The very thing you fear, Doubtful — that you won’t want to engage with the kid — is probably the very thing that will emerge as your superpower. You know what not to do. You know how not to treat a child. You know, because you’ve been that child yourself, and you know what a child really needs. Your own experience as a kid — and your ability to tap into what felt wrong, what hurt the most, what shattered you — will steadily guide you. You won’t want to hand that old pile of pain to your own kid. Trust me.

Don’t be fooled. It can be fucking lonely. So lonely. The loneliest. Especially if you wind up solo parenting.

But from that loneliness comes a rare chance to regard and befriend yourself in the thickest, darkest, dankest forest. You will find reserves of patience that you didn’t know you possessed. And if you allow it, your kid can lead you, like a magical little elf, to a clearing in the woods where you will run smack into yourself, regard this soul-sister with tenderness and compassion, take your own hand, and find the power to steadily stare into the dark woods at the abusers, rapists, and monsters who lurk there, and calmly say: We don’t have time for you anymore.

I am surrounded by parents right now.

Not gonna lie, every single one of them is grappling with their own inner child, and navigating the dark forest of their own difficult pasts.

This is another thing I’ll remind you: your entire social circle will shift if you have a kid, and you’ll be surrounded by the parents of the kids your child’s age in your community. This can be so confronting as well, as you navigate strange new friendships based on coincidence (Your kid is 5! My kid is 5! We are weirdly friends all of a sudden!). And you may find that people who don’t have kids — even your oldest, nicest friends — cannot understand your life, your priorities, or your problems.

They may not understand, most importantly and further to our conversation about trauma, how your relationship with yourself and your past is undergoing an entire overhaul. If you wind up having a kid and you’re remembering this letter years from now, please have patience with these people. They are the Quantum You who did not have kids, and they’re going through their own experience. But get ready for it: You will be in a cult of parents.

On the flip side, you’ll have a capacity for understanding People With Children that is hard to explain until you’ve been a parent. It’s a bit like trying to explain what it’s like to be high to someone who’s never been high. Only a person who has been high knows how to actually help out a person who is high as they are trying to find their car keys. There is a similar code among parents. You will never again feel exasperated at a woman with a screaming baby on a plane. You will just be filled with pity, because you will have been that woman.

………..

My older brother died when I was about 20. I often wonder if seeing my parents lose a child put me on the fence and made me scared to procreate, but I don’t think so. If nothing else, I find myself thinking of time spent with Ash not as an “investment” but simply as a pleasure, a simple pleasure in this simple moment.

I’m a morbid artist. I spend plenty of time thinking about how I would feel if my kid were taken by cancer or a car accident. I close my eyes and imagine how it would feel. And find myself thinking: I will have gotten to spend some amount of time with this amazing little person. I will have gotten three years with him. Five years. Seven. Ten. Fifteen. I try to take enjoyment in his company. Not a a job I have to do well so that I can win points as a Good Mother, but more as a strange gift that was bestowed upon me. This kid killed my ego, and killed my career and saved me from my own ambitious hamster wheel, and I appreciate him for that.

You wrote, “When I think of myself 10 or 20 years from now, I see a mom.”

I think you’re answering your own question here, in a way, Doubtful. If this is what you see: follow your instincts. And be ready to do it no matter what happens. Know that you may have to do it alone. Maybe you just need someone to give you permission. If you need that permission. I’ll give it to you. I did it. It was hard, but I made it.

I do not regret it.

And you will not regret it. Or perhaps, more honestly, you may regret it, but that regret will be a small side dish. The main dish will be an entirely new version of you.xx You’ll be somewhat unrecognizable to yourself. You’ll heal in unusual ways. If you are ready to go on that particular ride, to shed your current self, then do it. Go. You don’t get to pick who you give birth to, and you don’t get to pick who you become next, but you’ll very likely have a heart and ego that change shape dramatically and you won’t fit your old clothes.

If you choose not to do it, my friend, please know that I’ll celebrate you in equal measure. Maybe even more. If you need permission to just let the kid idea fly out the window, I give you permission in droves. In some ways, it’s a bolder choice — given society’s judgmental habits — to not have kids. I will remind you that kids are not a magical wand or silver bullet that will heal your trauma. There are so many paths to healing, and so many of them do not involve making another person. Kids may take you on a healing journey, sure. But anyone who tries to guarantee you that? Lying, or fooling themself.

On top of all that: if you get pregnant and something changes in your heart and you decide to have an abortion, I’ll celebrate that, too. (Though I feel for y’all over there in Nebraska, at the moment. You might have to fly to New York. I have a couch.) If you wind up having a miscarriage, or multiple miscarriages, I will celebrate you for having the strength to get through it. It’s hell.

With every pregnancy comes the possibility of complications and miscarriage, and it can be a really scary and, again, a very lonely experience. Please break the taboo and tell people what’s happening. Don’t keep your pregnancy a secret. Don’t wait three months. Tell the people who matter immediately. Pick a few friends. Tell the people who you want to be there for you if you miscarry. That way, you will not be alone. I’ve been through all of these experiences — miscarriage, abortion, medical scares during pregnancy — and they are all lonely as hell next to having a baby, when everybody calls and supports you.

I am here to remind you that every one of these experiences is equally valid … and you’ll hopefully find the people who understand that, and don’t just wanna show up at the Yay Baby party.

My dear Doubtful, whatever you are in 10 or 20 years, it’s going to be the right thing. Move with compassion — for yourself, for your partner, for your trauma, for your kid (if you decide to have one), and for all the parents and kiddos of this world. Every single one of them is navigating the great unknown and making it up as they go along.

You are not alone.

Whatever you do, promise me: no regrets.

Or rather, know that regret may lurk, but you can fully embrace whatever ride you take. Really. Every ride is the right ride to be on.

My dear, sweet L.H., doubtful friend from Nebraska…

You are safe.

You are loved.

Everything is fine.

With all my heart,

Amanda

P.S. I know you sent this letter many months ago, Doubtful. If you want to write back and let us know what happened and where you’re at, I’d love it. I am sure the comments will be filled with truckloads of advice from the readers as well. Read it all; every story is important. Everyone here is rooting for you. Including me, Sarah, and Coco.

………..

A text message from Sarah Beetson, frequent Ask Amanda illustrator, to Amanda:

………..

A bonus answer from Sarah:

Hello Doubtful in Nebraska,

First of all, I wholeheartedly agree that there are not enough stories, sharing, and support about those who are ambivalent over having kids. So much so that in my early 30s I created a private Facebook support group for the small handful of friends who were also sitting on the fence (or leaning yes, or leaning no.). I swayed like a pendulum from hard no to maybe to yes to hard no for 10 years, sometimes feeling downright horror at the thought of upending my career as an artist and the freewheeling lifestyle that goes with it in favour of total servitude to another human — to wondering if I should just do it — to being frightened off every time I took a long-haul flight and listened to a screaming child and witnessed its poor distraught parents. I’m an artist, work is my life and who I am, and I hated the idea of losing my identity. If I’m honest, I was a stone cold hard “no” for a lot of the time. A lot of the fears I had were of how I would be judged by others and how I would judge myself as a parent.

In contrast to you, Doubtful, I’m into the kid phase but definitely not a superfan of baby.

My nieces and nephews (seven of them) began arriving in quick succession, and I realised then that the baby phase scared the living shit out of me. A friend in New York told me that she had hated the first two years but afterwards enjoyed so much of her daughter’s childhood. I felt that. When the kids in my family hit 3 or 4, and started to come to auntie Sarah to get their nails painted or have me draw them a dinosaur, I suddenly related. Another dear friend, who is an incredible stepparent of two in their early 20s, ultimately did not decide to have a baby herself. Now older than birthing age, she once told me she occasionally gets a pang of wonder when she sees a mum with a young baby. But that’s all it is — an occasional pang.

We never had to actually make a firm decision. The Christmas before the pandemic hit, my partner and I decided to stop trying not to have a kid. We figured, we’ve never had a slip-up in 14 years, at 37 and 39 we probably can’t even get pregnant, and during lockdown when the contraceptives ran out, we just kind of went with it (although if I’m honest, it was partly conscious — a dear friend of mine on the other side of the world was suddenly pregnant and I hoped to share the experience from afar). And then, bang: April 2020. I got both lines on three sticks, and promptly began to dry-retch at the slightest whiff of coffee.

I remember being in the supermarket after our GP confirmed the positive pregnancy, staring at the frozen vegetables and realising I would never again have to feel the conflict of the question. It was done. An immense relief washed over me.

My pregnancy went smoothly, and birth was straightforward and natural and fine. But exactly as I’d anticipated, I didn’t greatly enjoy the baby phase, from the issues with feeding in the first four months to the sleep deprivation, and I certainly felt in survival mode for a considerable time. My son was a fairly early talker, and when he hit 18 months, I slowly realised I had started to enjoy it more. He’s 20 months now and speaks in three- or four-word sentences, and I love our bathtub baby-talk chats in the evenings, our mum ’n’ baby dance classes and baby soccer, and I even find myself loving his toddler friends, who are the same age as my kid and therefore I feel some kind of weird connection to.

I am sure all this has come alongside the fact that I’m back at work from home and in the studio three days per week (and can squeeze in the odd bonus email in naptime on the other days) and I’ve already reclaimed so much of myself. It’s a mahoosive juggling act, and time is a commodity almost as valuable as sleep these days, but it’s doable — and more straightforward and way less of a stress than I thought it’d be. It helps massively that I have a partner who is at least 50/50 on parenting and home life in general — I firmly would not have entered into it with a partner I had any suspicion would leave it mostly to me.

I think it is great to think about, if you do decide to go ahead, what are the things you are going to need to get you through the dreaded little-kid phase? If it’s after-school care to give you more time, don’t feel guilty for needing that. For me, to survive maternity leave, I knew I’d die inside without my art, so I set up three big paintings of flowers, outlined and ready to paint, during pregnancy, that I could pick at wherever possible after birth (my studio is in a shed a stone’s throw from our house). I would strap my baby to my chest whilst he slept and go sit at my easel and sometimes only get to paint a single thumb-size petal before I needed to change a nappy or lie down and rest myself. Chipping away at those artworks (they took me a full year to complete) honestly saved my maternal mental health. Maybe you have something you love to do that you could easily do with an older child? Even if they don’t naturally love it, if it’s something they get one-on-one time with you doing it, and you introduce it fairly early, they will probably get into it. My toddler knows that if he picks up a piece of chalk and goes to his easel at bedtime, he will get my undivided attention (and a bit more time before bed!) as we draw together, and he will happily sit through a full movie (film is my inspiration, though we are still limited to mostly Disney and Studio Ghibli) and snuggle in my lap. It’s all prone to change, but having a bit of a mental list has been good for me.

Some of the parenting process for me is about relinquishing control and trusting in the unknown. Bloody hard for people who have always had a game plan. I ticked a bunch of shit off my mental to-do list in my mid- to late 30s (artist residencies in Coney Island and Blackpool, check; trip to Vienna to see all of the Schiele/Klimt/Hundertwasser, check; art exhibitions of my work across continents, check). I made room in the life schedule without really acknowledging that that’s what I was doing, whilst simultaneously surrendering to the fact that things would probably never be the same again (though a lot of them have actually turned out to be doable post-baby).

In my many deliberations over about 10 years, one of the things that struck me was that in life, the only things I regret are things I haven’t said or done. Every silly decision has ultimately taught me something or led me to the path I’m on. Maybe I had a kid because of FOMO, but do I regret it? On the fifth wake-up of the night when my kid is sick/teething/having some kind of developmental fuckery/just wants a huggle? Not so far, I wouldn’t take it back. The love is kind of inexplicable. There’s always a bit of ambivalence, too — but now it’s the occasional thought of whether or not to give my kid a sibling, even though his dad and I have always leaned “one and done” (before and after we plunged into parenthood). Now I’m in all of the OAD Reddit support groups!

I fuck up constantly. During our sad and difficult breastfeeding journey, I googled every damn thing and felt shouted at by the internet and exhausted and overwhelmed that I could not fix the issue by researching it, or accepting what limited help is available on the Australian Medicare system. I had to ultimately relinquish control and surrender. I still battle with that daily, and I think that’ll continue to be my biggest lesson in this. I’ve found myself taking apart my own childhood and upbringing and attempting to re-parent myself in the way I parent my child, stripping away the shaming and the trauma where I recognise it in my past, but realising that my kid is going to also pick apart my parenting one day and that I can only strive to try to get it right.

I’m not gonna lie, Doubtful, sometimes (very, very often) the days are long and hard and I’m counting the hours till nap/bedtime just to get a moment to myself. Parenting is in some ways like those three paintings that took a year to complete, but in agonisingly slower motion. And then it’s contradicted during night cuddles with a kid who, you realise with a momentarily aching heart, will be too big to fall asleep on your shoulder like this in a year. It’s life on, by turns, the loudest and the quietest volume setting. It’s the old life and the new life. But I have never once wished I could go back and change my mind.

Love,

Sarah

Original artwork by Sarah Beetson.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The creation of this piece was funded and cheerleaded by the 10,000+ patrons at patreon.com/amandapalmer.com.

Here is the full insider post for patrons: https://www.patreon.com/posts/72651201

Please consider becoming a patron if you’d like to see more work like this in the world.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Email your questions to AskAmanda@gmail.com (please try to keep it under 300 words, and let us know whether or not you’d like to remain anonymous). We are reading everything, and thank you all for writing in.

I’m always reading all the comments.

1️⃣ To the larger question, "Should I or shouldn't I?":

I love both of my children deeply; they have become fantastic human beings who love me back (not always a sure bet!), and I'm proud of the parent I am and the people they are.

But if I had it to do over again, I would not have children.

(I hear everyone's gasps. Here's the thing: if I hadn't had them, I wouldn't miss them. It's okay to say this. It's okay to FEEL this.)

Getting pregnant and ultimately marrying someone with deep roots in a semi-rural area has meant giving up on many of my dreams. There are a hundred lives I could have lived, a hundred careers, a hundred paths I didn't take because I spent a full *quarter of a century* putting someone else's needs before my own.

I love them, but I gave up a LOT to be their mother, and I don't always think it was a fair trade. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I seem to be in the minority on this, but I thought it was worth bringing up.

2️⃣ To the trauma issue:

MASSIVE childhood trauma here. Neglect and abuse from a mother with BPD. A broken home at 9. Abandoned by my father after the divorce. Physical, mental, AND sexual abuse from various family members. THREE stepfathers and a dozen "not quite but almost" stepfathers. More than 30 moves (with accompanying school changes) before I was 16.

My childhood was a fucking TRAIN WRECK.

But here's the good news: it made me a better parent.

No joke — I am seriously not kidding — whenever I had to make a decision in my parenting journey, I asked myself "What would my mother have done?" and I pretty much did the opposite (or at least not THAT).

It worked. That's all I can say. It worked.

It's a fucked-up compass, but it got us all through.

So if you DO choose to have a kid, it'll be okay that you don't know what to do with them from 2-10, because at least you'll know what NOT to do with them!

I wish you so much luck and love, and I'm sure you'll do the exact right thing, whatever it is.

My birthed kids are 23 and 12, the first one very unplanned, the second one planned for years. I have 2 stepsons now as well.

I have nothing to add to the amazing, soul-piercing advice above other than this:

You might not like kids. But you’re gonna like YOUR kid. YOUR kid is gonna pick up your mannerisms and speech patterns; your humor and fun. YOUR kid is going to drive you nuts but in ways you recognize. The alchemy of “so like me” and “so much themselves” is a goddamn delight. I was scared to death of preteens. My preteen is fucking awesome. Because it’s still HER.

BLESSINGS on all of us, parents or not, agonizing or at peace. Life is so hard and gorgeous.