Hello all! Welcome to ASK AMANDA #1. I will be here all of February, reading and responding to comments. Comments are open to EVERYONE. Please be kind.

……………

Hi Amanda.

I’m dying of cancer at 39. Yes, it’s very sad, thank you.

My husband, and love of my life, Jason, is finding himself very much afraid of the crippling grief he expects will follow my death.

I know you spent some time in a similar situation with Anthony. How did you get through that fear and what advice would you give to my husband, or your younger self, about how to face it?

Thanks very much.

Penny

……………

Dear Penny,

Wow. Okay.

I don’t know how aggressive your cancer is, and I hope you get this in time. I’ve been sitting here for a few weeks reading the hundreds of letters that came into the Ask Amanda address, and although many of them feel more urgent than others, yours stood out. (And also, I’d love it if you wrote back to let me know that you got this, at AskAmanda@gmail.com.)

First, I just want to say this: I love you, Penny, and I’m thinking about you right now as I type this from my desk in New Zealand.

What a strange world, isn’t it? What happens and what doesn’t happen, and what we do with what we’re handed. I am wondering how you are feeling at this very instant, how your body and heart are doing, and I’m hoping that you’re not in too much physical or emotional pain.

I can tell that you are not looking for my sympathy. So I won’t do that or say the sorts of things that I imagine you’re hearing a lot right now.

I’m not an expert on death and grieving; I’m just a musician writing an advice column. But I’ll stop clearing my throat and give this a go.

I’ve been around a lot of people who were sick and sometimes dying. You mentioned Anthony, which means you’ve probably read my book The Art of Asking. For readers who don’t know: Anthony was a cross between a mentor, a parent, and a best friend to me, and he was a big part of the book. He died of leukemia right after it was published, after a four-year struggle, and only three months before my only child, Anthony (Ash for short), was born.

I was lucky to have had a moment to prepare emotionally. Anthony was suffering physically so much by the end that there was a bittersweet sense of relief. Four years is a long time to watch someone face off with cancer and death. I spent four years knowing that, barring a miracle, I would probably lose my best friend and confidant. I’d never be able to talk to him again, never be able to regale him with an amusing story or ask for advice, never be able to send him into a giggling fit with one of our immature in-jokes, never again walk through our favorite spot in the woods, or feel his comforting arms around me in a compassionate hug when I was wounded and hurt and just needed to be held quietly by someone who really, deeply understood me.

When Anthony finally died, I walked around in a trance for several weeks. I often couldn’t think straight. Nothing felt normal, or real. And mostly I remember feeling really, really, really lonely. Going into a coffee shop or a grocery store felt like entering a dark and horrific fun-fair; I couldn’t believe that everything could just be rolling along in its mundane way, when things in my heart were so catastrophic.

There’s a thing you and your letter just made me remember.

Something that happened the day after Anthony died.

It was June 2015. I was working in London and hugely pregnant when I received the phone call from our mutual friend Nicholas. I think it’s very close to the end, you should come. Now. Trust me. I grabbed a cab to Heathrow and was on the first plane to Boston, and raced in a taxi to Anthony’s home — right across the street from the house where I grew up, and where my parents still live. Even as the taxi pulled up into his driveway I wondered if I would miss the moment. The last moment.

I didn’t. Anthony was in the living room lying in a hospice bed, barely able to speak. His wife, Laura, was there. His closest friends and family. We gathered around him. Counted moments. Took turns by his side. Sometimes Nicholas would take out a guitar and we would sing. We all just sort of ... circulated — trying to figure out how to be around a dying person and all this grief. I spent the nights sleeping in my childhood bed, across the street from where Anthony had always been, from where he was about to leave. He died in that room a few days later.

When it happened, it felt like a strange dream — impossible, but true. The next morning was the solstice, the longest day of the year. I left my childhood home, walked across the street, and sat in the living room with Anthony’s body. I looked at him. It wasn’t scary. It was peaceful.

Since I know you’ve read The Art of Asking: Do you remember the scene I wrote in which my Kickstarter hit a million dollars and I’m too distracted by my goddamn phone to listen to Anthony tell me about his cancer-suffering? (I was such a dick.) That all took place at Peet’s, our local coffee shop. Anthony had been a daily regular there for years. The day staff all knew him, and they knew me. We clocked at least 500 hours at those little circular tables, talking about everything under the sun. It was our spot.

On the day after Anthony died, I walked the 10 minutes into town and into Peet’s, to get a comforting flat white coffee and a banana muffin because I was grief-stricken and deserved treats.

The guy behind the counter was Sam. I knew him, kind of. Sam was a shaggy-haired, tattooed, bespectacled artist in his early 20s, and he had developed an affectionate relationship with Anthony over the years he’d worked there.

Anthony had introduced us — with a kind of fatherly pride — because he knew Sam was an emerging musician, and we’d all joke with each other across the coffee counter. Sam was in a band, a songwriter, and had a wry sense of humor. He’d given me links to his music and I’d given him words of encouragement. Anthony and I would sit at our little table at Peet’s for over an hour sometimes, talking, crying, bickering, showing each other things on our phones, trying to untangle feelings and life and death. For the past four years, we’d been sitting at that table knowing that our hours might be numbered. Sam was often there, a few feet away at the counter, aware of us but not ever listening to the actual conversation. I would take Anthony’s loyalty card and go up to Sam at the counter to fill up Anthony’s teapot and order myself a second and third coffee, and yet another muffin (which I always deserved, because my life was always hard and I always deserved another muffin). Sam and I would exchange pleasantries and fist bump.

I barely knew Sam. I just really liked him. Sam the sweetheart.

And Sam was coincidentally working at the counter when I walked into Peet’s that day after Anthony died.

I was wearing sunglasses, I remember (it was the longest day of the year, it was sunny, it was hot), and my eyes were swollen and red from having cried the whole morning. Sam knew about Anthony and his cancer. We had discussed it occasionally in hushed tones the few times I’d been to Peet’s on my own. Sam didn’t know the details, but he knew Anthony was sick — knew he was dying.

I stood in line. Then it was my turn to order and I took my sunglasses off, and Sam looked at me and saw my red eyes. And the words got stuck in my throat and he said, “Anthony?” and I started sobbing, right there at the counter. I hadn’t sobbed since Anthony had taken his final breath.

It was like, in that moment Anthony really had died. Now he was really gone. And telling Sam had made it real.

Sam looked at me from across the counter, and his eyes got wet with tears. And we didn’t need to say much of anything. We just stood there in mutual grief, and knowing, and loving. Sam didn’t try to say anything conciliatory or dramatic; he didn’t offer me any platitudes. Maybe he said, “I’m sorry, Amanda.” But his tone was like yours, Penny, in your letter: Yes, it’s very sad. Thank you. This is it. We know this is it.

One of the things I’ve thought about a lot is how much permission we give ourselves, in this culture, to feel fear as a normal and acceptable emotion. And also: to really, truly grieve with abandon. To give grief the time and attention it deserves. I think we do a pretty terrible job of making space for that “crippling grief” you mention. Your letter was so short and your choice of words so perfect. It’s not just the crippling grief, as you say, but the fear of that grief. Something that’s “crippling” means that you cannot walk or move properly. And that’s exactly what happens when somebody you love dies. Sometimes, you literally cannot move.

But there is a way you can turn this coin of grief and see the other side, and the whole picture. The larger and more intense a love is, the larger the fear, the larger the grief. Love and grief are directly proportional, glued together, impossible to separate in scope and size.

To put it simply: the more Jason loves you, the more he’ll feel the grief, and the fear-of-grief. But there is a way where you can both step back in the landscape of your lives right now, and blur your eyes a bit, and notice that the degree to which he feels that fear is simply a measure of his love for you. That grief, that fear, is how much he loves you. You simply cannot feel love, real love, without welcoming in this dark flip side, this shadow. And if you can blur your eyes fully, you can maybe accept that it’s all one coin. That the fear isn’t “bad,” or a “price you pay,” or a “necessary evil,” or a tax (bad) on your love (good). It is the love.

This is hard to express in words, but what I’m trying to say is: that feeling of fear is a feature, not a bug. It’s there to show you, to teach you. It’s there to explain the size of the love.

There’s a Buddhist-inspired saying that “Pain is inevitable, suffering is optional.” The point is, you cannot — and should not — escape the very human and very necessary pain of grief, but perhaps you can escape the suffering that comes with it, riding shotgun: that fear of the pain, the fear of the grief. You both know the grief will happen. It has to happen. But the fear can, maybe, be more gently dealt with.

And so, let’s look at that. What is Jason afraid things will be like when you’re gone? What is he afraid will happen as he faces that crippling grief? And, perhaps, who will take care of him, and witness his grief, and be there for him, when he is in that crippling state of grief after you die?

In the days after Anthony’s death, I found that the most important thing for me was to be around the people who understood that Anthony had died and knew what it meant.

I am close to a lot of people, for sure. Family, friends, fans, patrons, staff, collaborators; I have dozens, even hundreds, of strong relationships.

But here was one of the hardest things when Anthony died: most of these people didn’t really know about or understand my relationship with Anthony. We were not part of one individual social circle. Even some of the closest members of my own family weren’t really aware of the depth of our friendship. It was weird. Everybody sort of understood that my best friend had died. But I didn’t feel understood most of the time. The thorniest part of the grief, and the fear-of-grief, was the loneliness. The irony of the fact that the one person who would truly understand — Anthony — was the dead one.

I found that, in the years leading up to Anthony’s death, I desperately wanted to go to the world to tell the story: the story of Anthony and Amanda. I wrote about him in my book, I talked about him on my blog, I shared the cancer updates onstage, even if people had little idea what I was talking about. I did it to feel less lonely. I’d never talked very publicly before about this close, important friendship of mine. But all of a sudden, I had to. Because I knew I was going to lose it, and I wanted the world to understand why I was grieving when the inevitable loss finally came.

Back to the story.

What I really needed in that moment, in that coffee shop the day after Anthony died, was a Sam.

This person who I barely knew but who knew Anthony just enough, and who had seen — at a close but impersonal distance — how connected we were. Sam who didn’t know very much about me at all and didn’t know much about Anthony but who bore simple witness to the real depth of our relationship in a way that’s hard to describe.

Perhaps, to help Jason before you die, give him some witnesses. Figure out who the Sams are. Who the people are who know not just “Jason” and not just “Penny” but “Jason and Penny.” Who really knows the two of you? Who has borne witness to you as a couple? Who knows your love? Who’s really seen it? Who gets it?

Those are the people who Jason will need around — to witness, to make space for, and to honor his grief — when you go.

And if you wonder who these people are, or feel that there may be candidates for this position, get some clarity. Look around. Talk to each other.

Pick the witnesses, the Sams who make sense. Get on the phone. Stop at the shop. Have a dinner party. Zoom if you gotta. But tell the story. Tell the small and significant anecdotes of your era together, this love-and-grief story that really happened and is still happening. Don’t exclude the dark sides of the story, the pain. Show it. Dig deep, share the heart-truths, tell the trials and tribulations. Tell the love story. Maybe don’t give it all to one person. Spread it around. Diversify. Pick your moment, pick your media. I don’t know enough about your life to know how to advise, but you know who you are, and you’ll choose correctly. I’m a musician, I had a blog, I had a chosen family of weirdos and queers and artists. I told them.

This is important to say: Tell the stories to the people who want to hear them, who are listening deeply not to indulge you or because they pity you, but because they truly want to hear, and hold, and know. You need witnesses who have a profound, authentic, and loving curiosity about the story of Jason and Penny.

I think this will help Jason. I know it helped me with the fear. He will need to be seen by people who understand what the loss is, what it means. What the meaning of the Penny-shaped hole is for him. And then, maybe, he will be allowed to walk around in his real and inevitable — and necessary — crippling grief feeling a fraction less lonely.

Another thing: These witnesses may not be the obvious candidates. It may not be who you think it’s gonna be. It could be a Sam at the coffee shop. It could be a therapist. A choir leader. A neighbor. An old friend. An aunt or uncle. It may be someone who comes to the story with no baggage attached. You just don’t know who is capable of being this sort of witness, this sort of receptacle to a story of love, until you ask or try it out. Don’t go looking where time and attention isn’t available. People have their own problems, their own dramas, pains and preoccupations; you cannot expect that it will be what it’s “supposed” to be, if you know what I mean. It may surprise you what happens. You need to ask to find out. You’ve read my book; you get the drift. Ask. Now more than ever. You are dying. You are allowed to ask. So ask.

I have a musician friend named Zoë Keating who lost her husband, Jeff, about eight years ago to inoperable lung cancer. They had a son, Alex, who was four.

Zoë has been one of my lifelong heroes: as a mother, as a working musician, as a survivor and dealer-with-er of a terribly shitty situation … she’s just an incredible person. She and I talk a lot about life and grief, and time, and kids, and how we handle things. She told me a few years ago that she wished that widows could still wear black for a year after their partners died, because she just couldn’t deal with having to explain this shit over and over. That her husband just suddenly died, tragically and way too young. Yes, it’s very sad, thank you. And that yes, she was now a widow with a young child, dealing in real time with the shock and awkwardness that other people had to deal with in her presence. And goddamn it, Zoë said, if she could’ve just gone old-school and gotten to wear black for a year, it would have been really handy.

Jason won’t be able to wear black; we don’t do it that way. Our culture has really fucked up how we deal with birth and death (and cancer, and chronic illness, and miscarriage, and abortion) and how we signify what people are going through. Most of us don’t sit with the dead body anymore; most of us don’t sit shiva for seven days while everyone in the community slows way down to create space for the sadness. And this lack of space, this disconnect, feeds the fear-of-grief — hammering another nail into the collective coffin of our separateness.

It seems to me that the next best thing we can do (unless we want to be real freaks and print Jason a set of rotating T-shirts saying “Hey, the love of my life just died of cancer, please be gentle with me and don’t make it weird, okay?”) is to arm your chosen community — whether it’s the family, the coffee-shop Sam, the grocer, the neighbor, the church folks, the book club, whatever — with the understanding that this is happening, and Jason will need you to understand. You can sew together the metaphorical black veil and give that to Jason before you go.

You cannot stop the dying. You cannot control that. And neither can Jason. But you can control what the world around him might be shaped like when you do go, and you can help shape that world into a place that can hold him a little more gently and honor the story of you — you two, your enduring love story. Jason will carry that story with him forever, till it’s his turn to die, and the more witnesses to the story, the better.

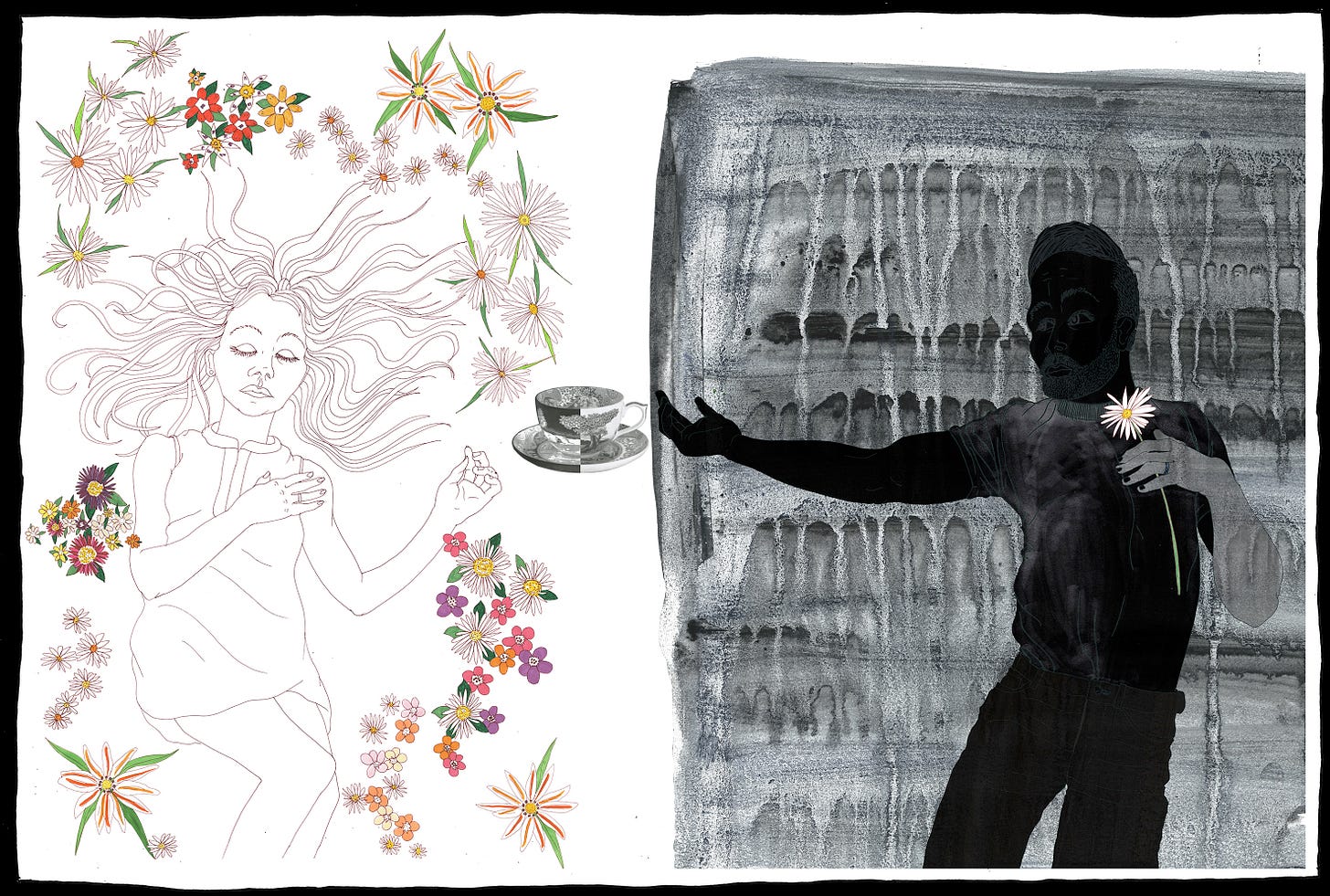

All these people reading this letter, we’re seeing it. Sarah Beetson — the illustrator/artist I’m working with on this column — read your letter and this response, and she made a drawing inspired by your and Jason’s story. She sent me a dozen drafts, working in her studio in Australia while juggling her new baby, while I juggled being on a hectic road trip with Ash. Sarah and I left each other endless messages, talking about you and Jason and what kind of image we think might move you. My assistant, Michael, who’s in Brooklyn, read an early draft of your letter and my response and said that it brought him to tears. I sent a near-final draft to my friend Kya in New Zealand and she said it made her cry over her lunch break.

And on and on. Your and Jason’s love story has already become more real to more people, and it has inspired us to feel a little deeper. And the story will keep going, as people read this letter and comment on the post.

Right now, maybe, for you: I am Sam. (Sam-I-am!) Maybe, for just a minute here, we can all be a Sam for you and Jason, here in this little corner of the internet. The internet, this advice column, and the readers — y’know … it’s just a bunch of real people with real feelings. They can hold you, too, if they want to.

I love you, Penny. I hope I get to meet Jason someday, and if we are lucky, perhaps I’ll meet you before it’s your time to go.

Oh, and one last thing: You called Jason “the love of your life.” That is so rare, you know that? So many people never get to say those words, and mean them. You won the lottery there, you two.

So I’m sending a heart-hug to you both, and I hope you both stay as safe from suffering and fear-of-grief as you can. I hope you get to drink deeply from one another’s loving company, I hope you find the Sams, I hope things are not too hard.

And please know, Penny, and Jason, that we’re all here thinking about you. We’ll be a Sam if you need us.

And to everybody reading: thank you.

Be the Sam you want to see in the world.

With all my heart,

Amanda

Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand

February 2022

HOUSEKEEPING & CREDITS

Comments and discussion are encouraged here. Feel free to talk to strangers. Please be kind, and please share this letter if you feel moved to do so. Also, please subscribe! It’s free — unless you want to pay a few extra dollars and get an audio clip of me reading my response and adding a few extra thoughts.

Next week, I’m going to try to attack all the pandemic and vaccine/anti-vaxxer pain. We got a lot of letters about that. Or maybe I’ll switch tacks and just answer all your painful questions about sex. I don’t know yet. Anyway: if you have a question, you can email it to AskAmanda@gmail.com, and please try to keep it under 300 words and let us know whether or not you’d like to remain anonymous. We are reading everything, and thank you all for writing in.

Thank you all for supporting this experiment! I will be publishing Ask Amanda here on Substack once a week throughout February. We have already received a truckload of excellent mail, and I’m working through it. For the people who signed up at the $5 level (to get the audio version of this column), surprise! You are going to get VIDEO (and audio if you want it, too). Watch your inboxes; we will discuss. The first (beta! be patient) video is going to come out as a freebie to all, and then I’ll send it over the paywall to the $5 folks.

I’d like to thank a few people for helping me edit this first issue of Ask Amanda. I had help from Jamie MacPhail (Te Awanga, NZ), Catherine Robertson (Hawke’s Bay, NZ), Bijan Hosseini (Utah, USA), Kya Farquhar (Havelock North, NZ), and Jamy Ian Swiss (San Diego, USA), all of whom read various drafts online or in person, gave me heartfelt feedback, and offered their own advice on how to word, format, and title things. I would also love to thank my faithful assistant back in Brooklyn, Michael, for all his hard work behind the scenes. It takes a village, people. And a warning to all my friends this month: if I’m staying at your house or you think you’re just meeting me for coffee, you’ll probably wind up editing my goddamn advice column. It happens that way.

I love you all so much.

Ask away, and see you all next week.

xx

AFP

……………

The Art of Asking, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help, my New York Times best-selling memoir/manifesto, with a foreword by the amazing Brené Brown, is available here. Or please order it from your local indie bookstore.

I also read the audiobook myself and added some songs, and people seem to love it.

……………

Original artwork for Ask Amanda will be created every week by the wonderful Sarah Beetson, who is working out of Queensland, Australia.

This was so beautiful. My uncle died of a heart attack a few days ago and I am currently bearing witness to my aunt's grief. She is in her late sixties and has dementia. So she is continuously forgetting and remembering that he has passed, which is a special sort of hell. When she remembers, and is wracked with grief, I hold her hands and we cry. Then it gently turns into half-remembered stories of their adventures. She describes to me the best she can with her flailing mind how much she loves him, and it feels even more honest and true and visceral because she cant find the right words. As if there simply are no words to describe the depth of their love and her grief. Thanks for helping me make sense of the role I've taken on. ❤❤❤

I read this as I too am a ‘Jason’ in the most literal sense. My husband has stage 4 cancer, and is slowly dying. I was not, nor ever will be ready to face this fact at age 42, that one day in the future, I will be alone. That I will be navigating my life alone.

Thank you Amanda for choosing to respond to Penny’s letter, and for our sound advice. Thank you to Penny for being vulnerable at a time you could choose to be selfish and thank you Jason, for holding space in a relatable way that seems only few understand.